Refactoring Pulumi Code with `aliases`

Posted on

Guest Article: Ringo De Smet, Founder of Cumundi, standardizes on Pulumi for writing infrastructure as reusable code libraries for his customers. Pulumi enables him to rapidly iterate through the build-test-release cycle of these building blocks.

Cumundi helps companies adopt cloud infrastructure in a more integral way. It has found that 75% of companies’ needs are covered by ‘vanilla’ infrastructure patterns. However, due to a shortage of people and time, there has been limited investment to take full advantage of cloud-native configurations - which can lead to inefficiency, poor performance, and higher costs.

How Pulumi Code Keeps Up with Changing Requirements

At Cumundi, we build reusable libraries for our customers to set up their infrastructure while following best practices. These best practices include a range of “non-functional requirements” - infrastructure patterns - which often receive less focus than application features. Where feasible, Cumundi encapsulates these non-functional requirements into infrastructure code libraries. This enables Cumundi to serve clients using all major clouds while keeping application-focused infrastructure libraries clean and modular.

It may come as no surprise that we also use Pulumi to manage Cumundi’s own infrastructure. As a young company (founded January 1st!), it is hard to foresee how our infrastructure needs will evolve. With Pulumi, we write code in a modern programming language, and, good coding practice is not to optimize prematurely because the future is unpredictable. Another coding best practice is red-green-refactor or formally known as Test-Driven Development. You take the current code, write a test for the new requirement, which initially fails (red). Next, you implement the code in the most straightforward way to make the test succeed (green) and you complete the cycle by refactoring the code to keep the design in proper shape.

This blog post demonstrates a TDD cycle for Pulumi code with a reduced version of the code used to configure the internal infrastructure we provide for each customer. This example focuses on one specific Pulumi resource property: aliases.

All the code is available on Github if you want to follow along with a full project setup. Every step described here is committed as a separate branch with the starting point on master, the default branch.

The Starting Point

Every Pulumi project starts empty, so ours is no exception. This is how our main Pulumi code file looks for now.

import * as pulumi from "@pulumi/pulumi";

const config = new pulumi.Config('gitlab')

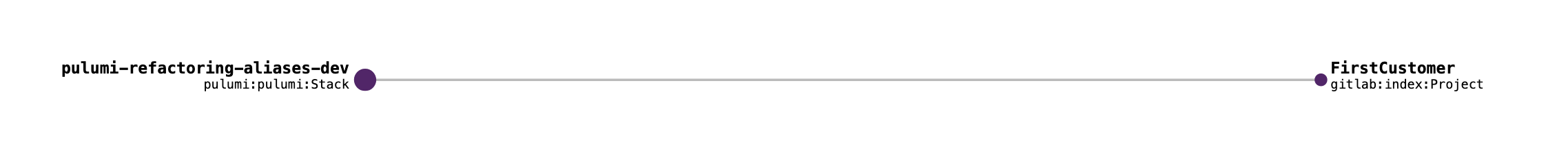

Applying the above code does nothing, which you can see in the Resources tab on the hosted Pulumi platform:

Adding the Git Repository

We create a separate repository for each of our customers:

const config = new pulumi.Config('gitlab')

const gitlabNamespace = config.getNumber('namespace')

const firstCustomer = new gitlab.Project("FirstCustomer",

{

name: "first-customer",

description: "First Customer code",

namespaceId: gitlabNamespace,

visibilityLevel: "private",

defaultBranch: "master",

pipelinesEnabled: true,

issuesEnabled: false,

wikiEnabled: false,

snippetsEnabled: false,

containerRegistryEnabled: false,

mergeRequestsEnabled: false,

mergeMethod: "ff",

onlyAllowMergeIfPipelineSucceeds: true,

sharedRunnersEnabled: true

}

)

We wrote the code in the simplest way to get the job done. After pulumi up, the Gitlab project is created:

A Customer Needs Cloud Infrastructure

For our second customer, I just duplicated the creation of the Gitlab repository and created a Google Cloud project and service account.

const secondCustomer = new gitlab.Project("SecondCustomer",

{

... // properties here

}

)

const secondCustomerProject = new gcp.organizations.Project("SecondCustomer",

{

projectId: 'second-customer',

name: 'Second Customer Infrastructure'

}

)

const serviceAccountSecondCustomer = new gcp.serviceAccount.Account("ServiceAccountSecondCustomer",

{

accountId: 'secondcustomer',

displayName: 'Service Account for Second Customer project',

project: secondCustomerProject.projectId

}

);

const serviceAccountSecondCustomerKey = new gcp.serviceAccount.Key("ServiceAccountSecondCustomerKey",

{

serviceAccountId: serviceAccountSecondCustomer.email

}

);

const secondCustomerGitlabCIVariable = new gitlab.ProjectVariable("SecondCustomerGCPAccess",

{

project: secondCustomer.id,

variableType: 'file',

key: "GOOGLE_APPLICATION_CREDENTIALS",

value: serviceAccountSecondCustomerKey.privateKey.apply(value => Buffer.from(value, 'base64').toString('utf-8')),

protected: true,

environmentScope: "*"

}

)

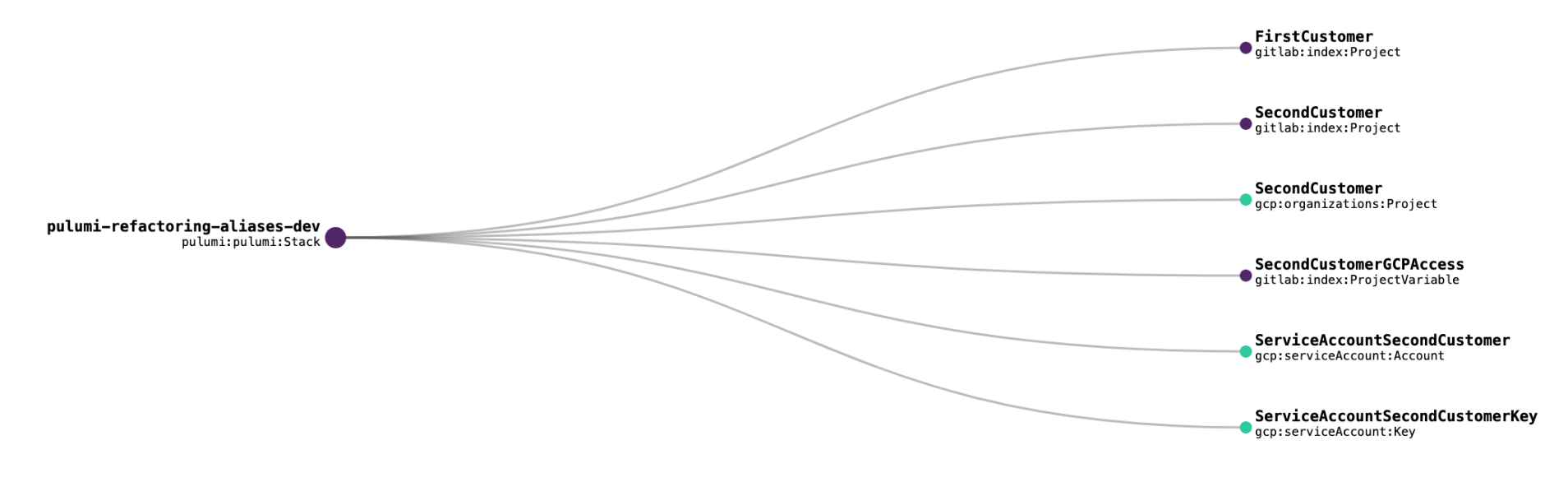

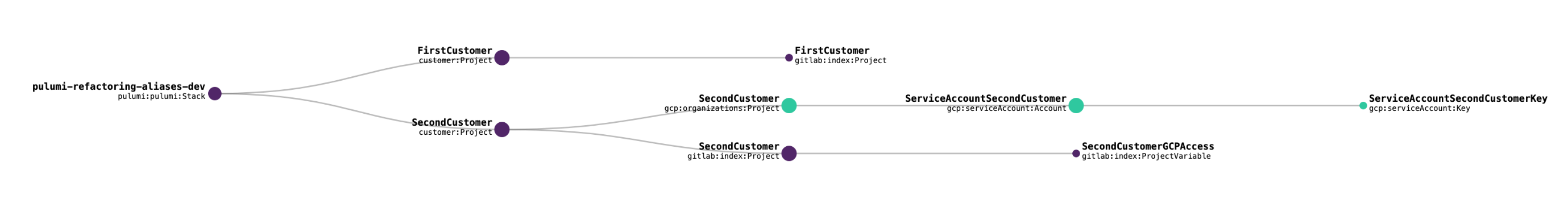

These resources are all added with the Stack as their parent in the resource view, as seen below. This is getting clumsy.

Visualization goes a long way, but a flat list of resources does not clearly show what belongs together.

Find Relationships between Resources

In the current state of the code, we created a Google Cloud service account and a key. Since a key can’t be created without a service account, we also created a Gitlab CI project variable for the Gitlab project of the second customer. Two cases of a parent-child relationship.

Although we have this relationship between our resources, the Pulumi state graph doesn’t display it. How can we change this without affecting the real resources on Gitlab and Google Cloud?

We can pass CustomResourceOptions as the last argument to every Pulumi resource that we want to create and use parent and aliases for refactoring.

To link the key to the service account, we set the parent property to the service account resource. If you run pulumi preview, Pulumi wants to recreate the key. It wants to do this because it searches for the key as a child resource of the service account. In your last applied Pulumi state, that is not the case.

const serviceAccountSecondCustomerKey = new gcp.serviceAccount.Key("ServiceAccountSecondCustomerKey",

{

serviceAccountId: serviceAccountSecondCustomer.email

},

{

parent: serviceAccountSecondCustomer

}

);

How can we tell Pulumi that the existing key resource fulfills the expectation in our code? The aliases property comes to the rescue!

If you want to rename resources in a Pulumi state or change the parent-child relationships, then the aliases property is your friend. Let’s indicate in our code that the existing key resource, linked to the Stack, is the key of interest.

const serviceAccountSecondCustomerKey = new gcp.serviceAccount.Key("ServiceAccountSecondCustomerKey",

{

serviceAccountId: serviceAccountSecondCustomer.email

},

{

parent: serviceAccountSecondCustomer,

aliases: [

{ parent: pulumi.rootStackResource }

]

}

);

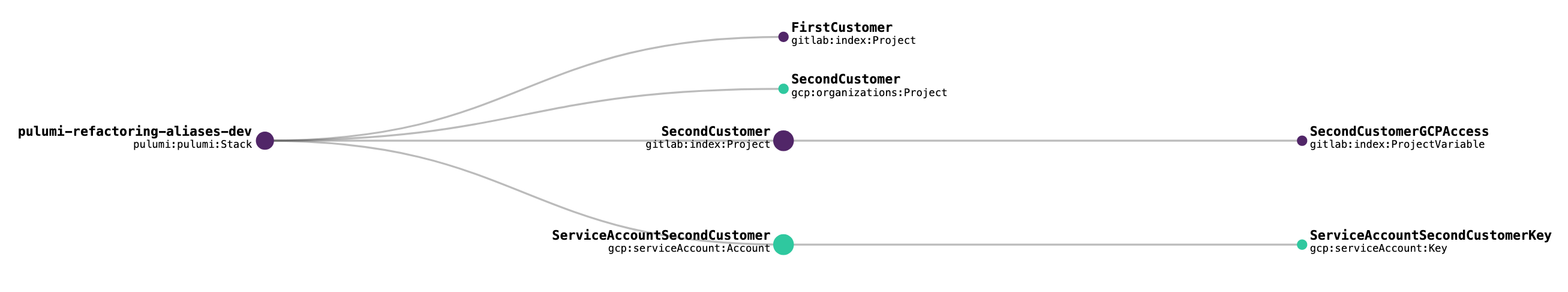

Before going forward, we also changed the relationship between the Gitlab repository and the Gitlab CI variable. When you run pulumi up, nothing changes on Gitlab and Google Cloud. But after applying the changes, refreshing the resource view on the Pulumi platform displays the following state graph.

Clean Up Duplication

In the previous step, I copied the code for the Gitlab repository from our first customer to our second customer. In this step, we resolve the duplication issue, and ensure that customer projects can conditionally create the Google infrastructure needed.

I introduced a ComponentResource subclass, which encapsulates moving the code for the individual resources into the customer resource class. As we set up Google Cloud resources for other customers, we create a Google Cloud project and related resources only when required. We can use a regular Typescript if conditional for this.

import * as pulumi from "@pulumi/pulumi";

import * as gcp from "@pulumi/gcp";

import * as gitlab from "@pulumi/gitlab";

import * as util from 'util';

export interface ProjectArgs {

// The name of the customer, e.g. "First Customer"

customer: pulumi.Input<string>;

// Indication whether we need to create Google Cloud infrastructure for this customer

needsGoogleInfra: boolean;

// Namespace in Gitlab to create the repositories in.

gitlabNamespace?: pulumi.Input<number> | undefined

}

// Pulumi custom resource representing a customer project

export class Project extends pulumi.ComponentResource {

constructor(name: string, args: ProjectArgs, opts: pulumi.CustomResourceOptions = {}) {

super('customer:Project', name, {}, opts);

var customerId = name.replace(/([a-zA-Z])(?=[A-Z])/g, '$1-').toLowerCase();

var serviceId = name.replace(/([a-zA-Z])(?=[A-Z])/g, '$1').toLowerCase();

const gitlabProject = new gitlab.Project(name,

{

name: customerId,

description: pulumi.interpolate`${args.customer} code`,

namespaceId: args.gitlabNamespace,

visibilityLevel: "private",

defaultBranch: "master",

pipelinesEnabled: true,

issuesEnabled: false,

wikiEnabled: false,

snippetsEnabled: false,

containerRegistryEnabled: false,

mergeRequestsEnabled: false,

mergeMethod: "ff",

onlyAllowMergeIfPipelineSucceeds: true,

sharedRunnersEnabled: true

}

)

if (args.needsGoogleInfra) {

... // Google Cloud and Gitlab CI Variable code here.

}

}

}

Now that I have our custom resource, I can use it for our existing customers. Our refactored main Pulumi file looks like this:

const firstCustomer = new customer.Project("FirstCustomer",

{

customer: 'First Customer',

needsGoogleInfra: false,

gitlabNamespace: gitlabNamespace

}

)

const secondCustomerProject = new customer.Project('SecondCustomer',

{

customer: 'Second Customer',

needsGoogleInfra: true,

gitlabNamespace: gitlabNamespace

}

)

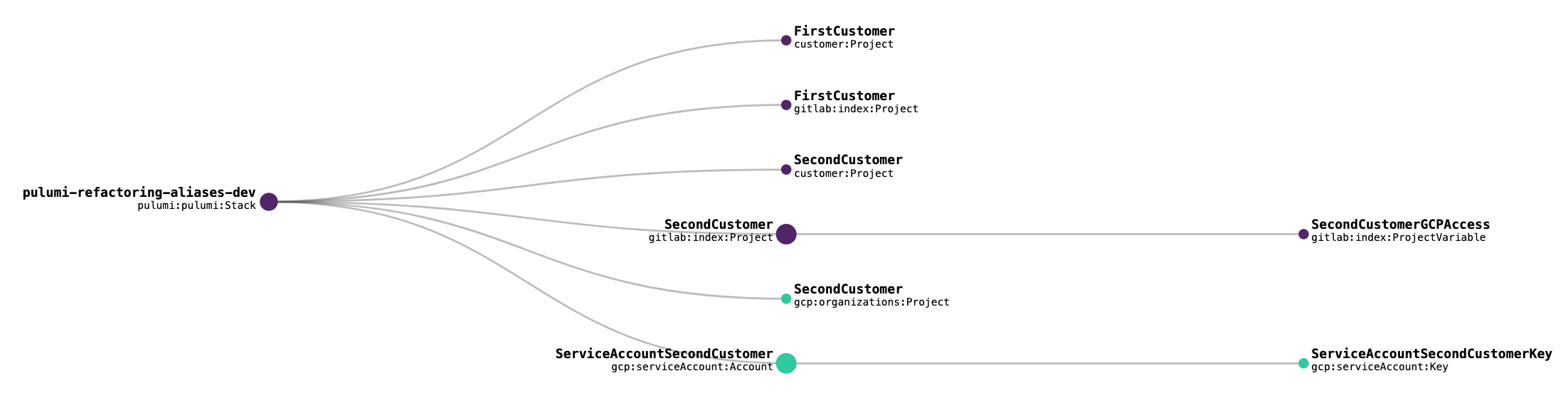

When we apply this to our infrastructure, two custom resources are created and saved to your Pulumi state.

However, we have not updated the parent-child relationships.

Fix the Remaining Relationships

We have a representation of a customer project in our Pulumi state graph, but we want to see the resources of each customer as child resources of this abstraction, right?

The same trick with parent and aliases is used to re-parent our resources. Our resources are created within the constructor of our Project class. In Typescript, the language used in this example, we can use the keyword this to point to the Project instance.

export class Project extends pulumi.ComponentResource {

constructor(name: string, args: ProjectArgs, opts: pulumi.CustomResourceOptions = {}) {

super('customer:Project', name, {}, opts);

var customerId = name.replace(/([a-zA-Z])(?=[A-Z])/g, '$1-').toLowerCase();

var serviceId = name.replace(/([a-zA-Z])(?=[A-Z])/g, '$1').toLowerCase();

const gitlabProject = new gitlab.Project(name,

{

name: customerId,

description: pulumi.interpolate`${args.customer} code`,

namespaceId: args.gitlabNamespace,

visibilityLevel: "private",

defaultBranch: "master",

pipelinesEnabled: true,

issuesEnabled: false,

wikiEnabled: false,

snippetsEnabled: false,

containerRegistryEnabled: false,

mergeRequestsEnabled: false,

mergeMethod: "ff",

onlyAllowMergeIfPipelineSucceeds: true,

sharedRunnersEnabled: true

},

{

parent: this,

aliases: [

{ parent: pulumi.rootStackResource }

]

}

)

While we are changing parent-child relationships, the service account resource is also updated to have the Google Cloud project as its parent. The result should look like the state graph below.

If another developer reads this code, they might not immediately have a clear picture of how everything is wired together. However, looking at the Pulumi resource visualization, the following properties can immediately be deduced:

- our infrastructure has 2 customer projects

- one customer only has a Gitlab repository, while the other also has Google Cloud infrastructure

- if we create a Google Cloud project, we create a service account and a key together with it

- if we create a Google Cloud project, we also set a Gitlab CI variable. It’s a pity though I can’t link the Gitlab CI variable to the key.

Next Steps

You probably noticed by now that the aliases property accepts a list. You can provide entries like:

{ name: <some old name> }{ parent: <some previous parent> }{ name: <some old name>, parent: <some previous parent> }

Note that putting the first two in the aliases list is not the same as putting the third one as the single entry. I leave it up to the reader to test it and understand the difference.

The take away from this example is: values for name in the aliases property can not be Inputs as they need to be resolvable at preview time, similar to the name of the resources themselves.

Conclusion

The Pulumi programming model well designed with regards to the evolution of an infrastructure. With ComponentResource and the parent and aliases properties, refactoring your infrastructure code is a breeze with visualizing abstractions on the Pulumi platform.