GitOps Best Practices I Wish I Had Known Before

Posted on

Getting started with GitOps can feel like trying to herd cats through a YAML factory while the factory is on fire. It’s one of those things that seems like it ought to be simple (just use Git!), but in practice is much more complex — and you may not realize how much more complex until you’re weeks or more into a project. After years of running GitOps workflows in production across dozens of clusters, I’ve collected a list of best practices that I’m hoping can save you from having to make many of the mistakes I’ve made. Think of it as the GitOps cheat sheet I wish I’d had from Day 1.

If you’re not familiar with the formal definition, the OpenGitOps project distills it into four principles:

- Declarative desired state

- Versioned and immutable storage

- Automatic pulling

- Continuous reconciliation

But those principles only define the what. This post is also about the how — the practical lessons that can make or break a GitOps implementation.

In this post, I’ll walk you through the GitOps best practices I’ve picked up from production experience, community talks, and more than a few late-night incident calls. Whether you’re just getting started with GitOps or looking to level up, these tips should help you avoid the potholes.

- Git is your single source of truth (no, really)

- Declarative over imperative, always

- Pull-based deployments are the way

- Separate app code from deployment config (when it hurts not to)

- Use directories, not branches, for environments

- Validate before you merge

- Tag with commit SHAs, not “latest”

- Automate drift detection and reconciliation

- Practice progressive delivery

- Policy-as-code: your automated guardrails

- Bridge your IaC and GitOps (don’t choose one)

- Be pragmatic, not dogmatic

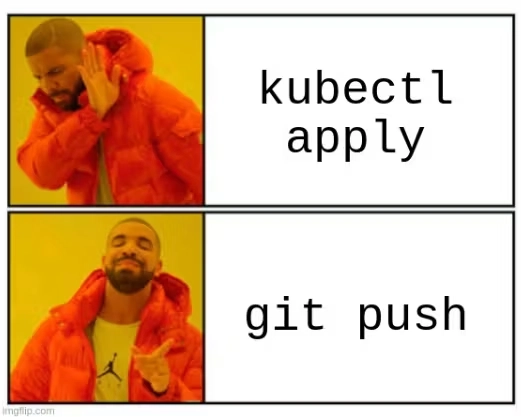

The GitOps mindset in a nutshell.

1. Git is your single source of truth (no, really)

This is the bedrock that the principles of GitOps are built on: every piece of your environment’s desired state lives in a Git repository. No exceptions. No “I’ll just fix it real quick with kubectl edit.” No “let me patch this configmap by hand because the PR process takes too long.”

The moment you make a manual change to your cluster, you’ve created drift between what Git says the world should look like and what it actually looks like. Drift will quietly wreck your GitOps workflows if you let it.

- Put everything in Git: Kubernetes manifests, Helm values, Kustomize overlays, policy rules, even your GitOps tool configuration itself.

- No manual

kubectledits. If it’s not in Git, it doesn’t exist. Period. Train your team to treat direct cluster changes like touching a hot stove. - You get an audit trail for free. Git gives you a complete history of who changed what, when, and why. That’s your compliance audit trail baked right in.

2. Declarative over imperative, always

If you’re still running sequences of kubectl create, kubectl patch, and kubectl delete commands to manage your cluster, you’re not really doing GitOps yet. Declarative means you define what you want the end state to look like, not the step-by-step instructions to get there.

Think of it like ordering at a restaurant. Imperative: “Go to the kitchen, grab flour, knead dough, preheat the oven to 200 degrees, shape the pizza, add sauce…” Declarative: “One margherita pizza, please.” Let the system figure out how to make it happen.

- Your manifests describe the end result. The GitOps operator reconciles reality to match.

- It’s idempotent by design. Apply the same manifest ten times, get the same result. No side effects, no surprises.

- Rollbacks are easier: just revert a commit. The operator sees the previous desired state and reconciles. A caveat though: this only works for stateless resources; database schema migrations, CRD version changes, persistent volume modifications, and rotated secrets don’t always revert cleanly by rolling back to a previous commit. Be sure to plan rollbacks involving stateful resources carefully.

kubectl commands, stop and ask yourself: “Can I express this as a declarative manifest instead?” Nine times out of ten, the answer is yes.3. Pull-based deployments are the way

Traditional CI/CD is push-based: your pipeline builds an artifact and then pushes it to the cluster. GitOps flips this. An agent running inside your cluster continuously polls a Git repository and pulls changes when it detects them.

Why does this matter? With push-based deployments, your CI system needs credentials to access your cluster. That’s a wide attack surface. With pull-based, the agent already lives inside the cluster and only needs read access to your Git repo.

- Tools like ArgoCD and FluxCD run controllers inside your cluster that watch your Git repos.

- Your CI pipeline never needs

kubeconfigaccess. The agent handles deployment. - The agent doesn’t just deploy once; it continuously ensures the cluster matches the desired state in Git.

Pro Tip: You may be tempted to set your reconciliation interval to something aggressive like 1 minute so you always know exactly which version is deployed. That works for a while, but at scale (200+ applications polling every minute) you can blow through GitHub’s API rate limits (5,000 requests/hour for authenticated users) and put real pressure on the Kubernetes API server.

A better approach: set up webhook receivers. Both ArgoCD and FluxCD support incoming webhooks from GitHub, GitLab, and Bitbucket. Your Git provider pings the GitOps controller on every push, so reconciliation kicks off in seconds instead of waiting for the next poll. That alone kills most of the API rate limit pain at scale. You can then relax polling to a 5 or 10 minute fallback for the rare case where a webhook doesn’t fire.

4. Separate app code from deployment config (when it hurts not to)

Let me be upfront: if you’re a small team with one or two services, keeping your Kubernetes manifests next to your application source code in the same repo is fine. A monorepo is simpler to manage and one less thing to automate. Don’t split repos just because a blog post told you to.

That said, ArgoCD’s official best practices call separate repos “highly recommended,” and there are real reasons for that once you grow. Application code and deployment configuration have different lifecycles. You might bump resource limits in a Helm values file without touching a single line of app code. Or you might refactor your entire codebase without changing any deployment parameters. In a shared repo, every config tweak triggers your full CI pipeline, and ArgoCD invalidates the manifest cache for all applications in the repo on every commit, not just the ones that changed. That cache invalidation alone can become a performance problem with dozens of apps in one repo.

- When config tweaks start blocking app code from getting through CI, it may be time to split.

- When different teams need different access levels (not everyone who pushes app code should modify production deployment config), it’s time to split.

- When you’re running microservices with independent release cadences that step on each other, it’s time to split.

If none of those apply yet, don’t split. You’ll know when the pain arrives.

5. Use directories, not branches, for environments

This is the number one anti-pattern I encounter in the wild. Teams create a dev branch, a staging branch, and a prod branch, then cherry-pick or merge between them for promotions. It sounds logical, but it’s a trap. Branches diverge, cherry-picks get missed, configs meant for dev sneak into staging or prod, and before you know it, your environments have drifted, and you can’t tell what’s actually different between them.

- A folder structure like

environments/dev/,environments/staging/,environments/prod/makes differences visible in a singlediffcommand. - Moving a change from dev to prod is just copying or updating files across directories, reviewed via a standard pull request.

- You’ll never accidentally skip a commit or introduce an environment-specific change where it doesn’t belong. No more cherry-pick roulette.

One thing to note: the commonly used rendered manifests pattern actually does use per-environment branches, but not in a human-managed way. In that pattern, config changes are still committed to main (using named directories as above), and an automated CI process pushes environment YAML to read-only environment branches, which ArgoCD reads from. If you want to try it, ArgoCD’s built-in source hydrator and Kargo Render can automate the rendering for you.

To keep things DRY, you can look to a tool like Kustomize, which lets you use a shared base environment and then apply per-environment patches. Your base directory holds the common manifests, and each environment directory contains only the differences. For example:

gitops-repo/

├── base/

│ ├── deployment.yaml

│ ├── service.yaml

│ └── kustomization.yaml

├── environments/

│ ├── dev/

│ │ ├── kustomization.yaml # replicas: 1, limits: 256Mi

│ │ └── patches/

│ ├── staging/

│ │ ├── kustomization.yaml # replicas: 2, limits: 512Mi

│ │ └── patches/

│ └── prod/

│ ├── kustomization.yaml # replicas: 3, limits: 1Gi

│ └── patches/

This minimizes duplication while keeping environment boundaries clear.

6. Validate before you merge

Catching errors after they’ve been applied to your cluster is expensive. Catching them in CI before the merge is cheap. Shift left as hard as you can.

Your GitOps CI pipeline should validate everything it can before the change reaches your cluster: YAML syntax, Kubernetes schema validation, policy compliance, dry-run rendering.

- Tools like

yamllintandkubeconformcatch syntax errors and schema violations before they become runtime failures. (Note:kubeval, which you’ll see in older guides, is no longer maintained — its own README points to kubeconform as the replacement.) - Run

helm templateorkustomize buildin CI to verify that your templates render without errors. - Use OPA/Conftest or Kyverno to enforce organizational policies (no privileged containers, required labels, resource limits set) before merge.

Here’s a minimal GitHub Actions workflow that validates your GitOps manifests on every PR:

name: Validate GitOps Manifests

on:

pull_request:

paths: ["environments/**"]

jobs:

validate:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v4

- name: Validate YAML schemas

run: kubeconform --strict environments/**/*.yaml

- name: Build and verify Kustomize output

run: |

for env in environments/*/; do

kustomize build "$env" > /dev/null

done

- name: Diff against live cluster

run: |

kustomize build environments/staging/ | \

kubectl diff -f - || true

kubectl diff step in your CI pipeline that shows exactly what would change in the cluster if the PR were merged. This gives reviewers a concrete view of the impact, not just the YAML diff.7. Tag with commit SHAs, not “latest”

Using latest as your image tag in a GitOps workflow is playing fast and loose with your deployments. You have no idea what version is actually running, you can’t reliably roll back, and your Git history becomes meaningless because the same manifest could deploy completely different code depending on when it was synced.

- Tag your container images with the Git commit SHA that produced them. This creates a direct link between your source code, your build, and your deployment.

- Once a tag is pushed, it should never be overwritten. No re-tagging, no “oops let me push a fix to the same tag.”

- Need to roll back? Just revert the commit that updated the image tag. The previous SHA still points to the exact same image it always did.

latest or any other mutable tag. Make it impossible to deploy without a pinned version.8. Automate drift detection and reconciliation

Drift is when your cluster’s actual state doesn’t match the desired state in Git. It happens when someone runs a manual kubectl command, when an autoscaler changes a replica count, or when a CRD controller modifies a resource behind your back.

The whole point of GitOps is continuous reconciliation. Your operator should constantly compare the live state against Git and bring things back in line.

- Configure your GitOps tool to automatically revert manual changes, but build your exclusion lists (the set of fields and resources you intentionally skip during reconciliation) before you turn on auto-sync, not after. Controllers like Istio, cert-manager, and Crossplane legitimately modify resources, and auto-remediating those changes creates reconciliation loops that can destabilize a cluster. Start with a conservative exclusion list and tighten it over time.

- Even with auto-remediation, you want to know when drift happens. Set up alerts. It might indicate a process problem or a team member who needs coaching.

Pro Tip: Be precise about what you reconcile. HPAs, VPAs, cert-manager annotations, and external-dns records all legitimately modify resources. Use ignore rules to exclude fields that are intentionally dynamic. In ArgoCD, that looks like this:

spec:

ignoreDifferences:

- group: apps

kind: Deployment

jsonPointers:

- /spec/replicas

- group: admissionregistration.k8s.io

kind: MutatingWebhookConfiguration

jqPathExpressions:

- .webhooks[]?.clientConfig.caBundle

Also, don’t overlook resource ordering. ArgoCD sync waves and Flux’s dependsOn let you enforce that CRDs are applied before custom resources and namespaces before workloads. Getting ordering wrong is one of the most common causes of failed syncs in production.

9. Practice progressive delivery

Progressive delivery lets you gradually roll out changes, verify they’re working, and automatically roll back if something goes wrong.

GitOps and progressive delivery fit well together. Your Git repo describes the desired rollout strategy, and controllers in the cluster execute it.

- Canary deployments: send a small percentage of traffic to the new version. If error rates spike, automatically roll back.

- Blue-green deployments: run two identical environments, switch traffic once the new one is verified healthy.

- Argo Rollouts extends Kubernetes with canary, blue-green, and analysis-driven rollout strategies that integrate with ArgoCD.

- Flagger is the Flux ecosystem equivalent, with automated canary analysis, A/B testing, and blue-green deployments using service mesh or ingress controllers.

- Kargo takes it a step further by orchestrating promotions across multiple stages and environments. Instead of manually wiring up pipelines to move changes from dev to staging to prod, Kargo automates the entire promotion workflow on top of ArgoCD. I did a deep dive on GitOps promotion tools and why they belong in your toolkit:

10. Policy-as-code: your automated guardrails

Reviews are great, but humans make mistakes. Policy-as-code adds an automated layer that enforces organizational rules before a change can land in your cluster. Think of it as guardrails on a mountain road: they don’t slow you down, they just keep you from going over the edge.

- OPA/Gatekeeper lets you define policies in Rego that the admission controller enforces at deploy time (e.g., no containers running as root, all deployments must have resource limits).

- Kyverno is a Kubernetes-native policy engine that uses familiar YAML to define and enforce policies, including mutation and generation.

- Starting with Kubernetes 1.26+, you can write CEL-based ValidatingAdmissionPolicies natively without any external tooling. A lightweight option if you don’t need the full feature set of OPA or Kyverno.

- Pulumi CrossGuard lets you write policy packs in TypeScript or Python that validate infrastructure before it’s deployed. If your IaC and GitOps layers are bridged (see the next section), CrossGuard can enforce rules across both.

- Run policy checks in your CI pipeline so violations are caught during the PR, not after deployment.

11. Bridge your IaC and GitOps (don’t choose one)

I hear this all the time: “We use Terraform for infrastructure and ArgoCD for deployments, and they live in completely separate worlds.” Sound familiar? Most teams treat IaC and GitOps as independent workflows, but they’re really two halves of the same story.

IaC handles “Day 0,” creating the cloud resources your cluster depends on: VPCs, the Kubernetes cluster itself, IAM roles, databases, DNS zones. GitOps handles “Day 2,” managing what runs inside the cluster: applications, addons, configurations. The gap between them is where things get messy. Your Helm charts need IAM role ARNs. Your GitOps-deployed addons need to know the cluster’s OIDC provider endpoint. That metadata has to flow from the IaC layer to the GitOps layer somehow.

The gitops-bridge pattern solves this cleanly: IaC provisions cloud resources and writes metadata (role ARNs, account IDs, endpoints) into Kubernetes resources (like ConfigMaps or Secrets) that your GitOps tool can consume directly.

- Keep each tool in its lane. Don’t force Terraform’s Helm provider to fight with ArgoCD over resource ownership.

- Pulumi lets you define your cloud infrastructure in real programming languages (TypeScript, Python, Go), which makes it natural to compute and pass metadata to your GitOps layer. You can use stack outputs to expose values like role ARNs and cluster endpoints, then feed them into your GitOps manifests. The Pulumi Kubernetes Operator even lets ArgoCD reconcile Pulumi stacks via GitOps.

- Statsig went from “1-2 devs clicking around cloud consoles with SEVs left and right” to fully self-service by using Pulumi to generate manifests and ArgoCD to deploy them.

- As you grow beyond a handful of clusters, think multi-cluster from the start. Patterns like ArgoCD ApplicationSets with cluster generators and Flux’s Kustomization targeting become important for fleet management. The gitops-bridge pattern works well here because your IaC layer can register new clusters and write their metadata into Kubernetes resources, which ApplicationSets automatically pick up.

Here’s how the gitops-bridge looks in practice. Pulumi provisions cloud resources and writes metadata into a ConfigMap that ArgoCD consumes:

# ConfigMap written by Pulumi after provisioning cloud resources

apiVersion: v1

kind: ConfigMap

metadata:

name: cluster-metadata

namespace: argocd

labels:

gitops-bridge: "true"

data:

aws_account_id: "123456789012"

cluster_name: "prod-us-east-1"

iam_role_arn: "arn:aws:iam::123456789012:role/app-role"

oidc_provider: "oidc.eks.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/id/EXAMPLE"

Your ArgoCD Applications or Helm values can then reference this ConfigMap, closing the loop between IaC and GitOps without hardcoding cloud-specific values.

12. Be pragmatic, not dogmatic

Michael Crenshaw from Intuit gave a talk titled “How GitOps Should I Be?” at a CNCF conference. Intuit runs 45 ArgoCD instances managing 20,000 applications across 200 clusters. The approach they took: “Be strategic, be pragmatic. GitOps most of the time.”

One of the largest GitOps adopters in the world explicitly deviates from pure GitOps when the situation calls for it. Dogmatic adherence to principles that don’t serve you is just another form of technical debt.

- Intuit found that GitHub’s SLA of 20 minutes meant they couldn’t rely on GitOps for region evacuation, so they wrote a

kubectlcron job that bypasses Git for failover. Pragmatic. - Massive Jenkins ecosystems don’t get rewritten overnight. Intuit’s compromise: the last step in the Jenkins pipeline calls

argocd app sync. It’s push-based, yes, but the source of truth stays in Git. The Jenkins pipeline doesn’t own the desired state; it just tells ArgoCD “go reconcile now” instead of waiting for the next poll. It’s a stepping stone while teams migrate off Jenkins, not a permanent architecture. - Continuous reconciliation with self-heal (auto-reverting manual changes) is where most teams deviate. In practice, many teams start with automated drift detection and alerting (so you know when someone runs a manual

kubectlcommand) but leave auto-remediation off until they’ve built confidence in their exclusion lists. That’s a reasonable middle ground.

Final thoughts

GitOps isn’t a silver bullet, but it’s one of the best approaches we have for managing Kubernetes at scale. The practices in this list aren’t theoretical. They’re what I’ve learned from running GitOps in production, watching talks from teams at Intuit and Statsig, and making every mistake in the book at least once.

If I had to boil it all down to one sentence: treat your GitOps repo like production code, because it is.

Start with the basics (Git as source of truth, declarative config, pull-based delivery) and layer on the advanced practices as your team matures. Don’t try to implement all 12 on Day 1. Pick the three that address your biggest pain points and iterate from there.

And remember, even the largest GitOps adopters in the world aren’t doing it perfectly. They’re being pragmatic. You should be too.

How Pulumi fits into your GitOps workflow

Several of the practices in this post touch on problems Pulumi is built to solve. If you’re bridging IaC and GitOps, managing environment-specific configuration, or enforcing policy across both layers, here’s where to start:

- Pulumi IaC: Define cloud infrastructure in TypeScript, Python, or Go and use stack outputs to feed metadata into your GitOps manifests.

- Pulumi ESC: Manage secrets and configuration across environments with fine-grained access controls, integrated with Kubernetes via the External Secrets Operator or the Secret Store CSI Driver.

- Pulumi Kubernetes Operator: Let ArgoCD reconcile Pulumi stacks via GitOps, closing the loop between your IaC and Day 2 workflows.