Testing Practices for Cloud Engineering

Posted on

Cloud engineering brings industry-standard software development practices to building, deploying, and managing cloud infrastructure. Testing is a common practice for evaluating software to ensure that it meets requirements. Similarly, infrastructure testing checks for missing requirements, bugs, and errors; it also ensures security, reliability, and performance. Testing uses manual or automated tools to identify bugs that can cause unexpected infrastructure behavior.

There are many benefits to infrastructure testing, including:

- reduced costs to fix bugs when caught early in the development lifecycle,

- discovering security risks and problems earlier,

- delivering a quality product that creates customer satisfaction through a great user experience

Testing shifts left the risk inherent with distributed architectures composed of many resources. Ultimately, testing increases release velocity, reliability, and confidence in your application.

This article is the first in a two-part series about testing infrastructure. The terminology for testing can be confusing because of broad definitions that overlap. This article will narrow those definitions that originated from application testing and apply them to infrastructure and cloud engineering. Let’s take a look at the different types of testing used with infrastructure as code.

Functional testing vs. non-functional testing

With infrastructure as code we want to test if parts of the system work as required or how parts interact with each other; this is functional testing. We will also want to test how the system behaves concerning performance, security, reliability, usability, and compliance. In general, these tests are called non-functional tests because they test the system’s behavior as a whole rather than by its parts.

In functional testing, unit tests typically test a single function or class. They are low-level tests that can be executed quickly and at low costs. Integration tests are functional tests that validate how components interact with each other, i.e.; it checks the interaction between software components. Non-functional tests are frequently performance tests, which evaluate the behavior of the system.

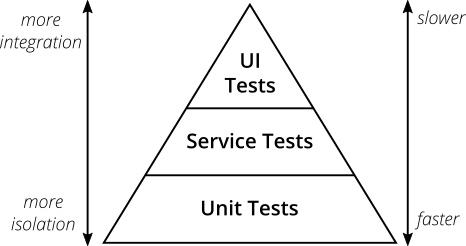

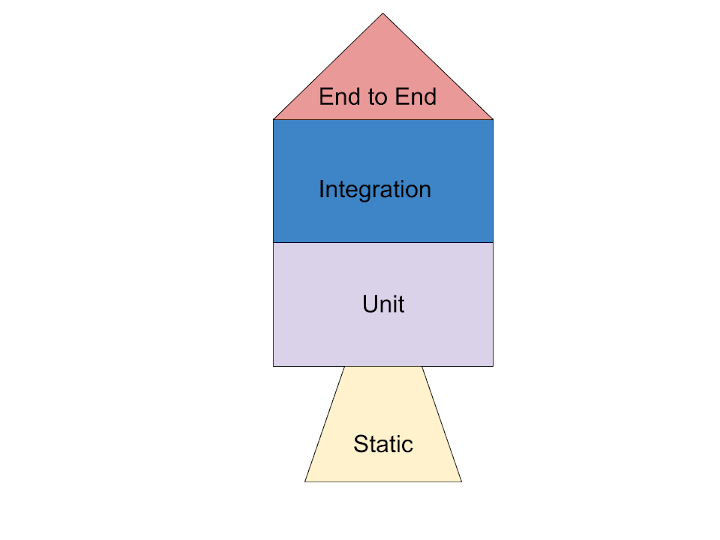

Mike Kohn proposed the testing pyramid that shows the different layers of testing and the amount of testing for each layer.

In their original form, unit tests comprise most tests, with integration or service tests as the middle layer of the pyramid. At the top of the pyramid are end-to-end or UI tests, which indicate performing non-functional tests sparingly.

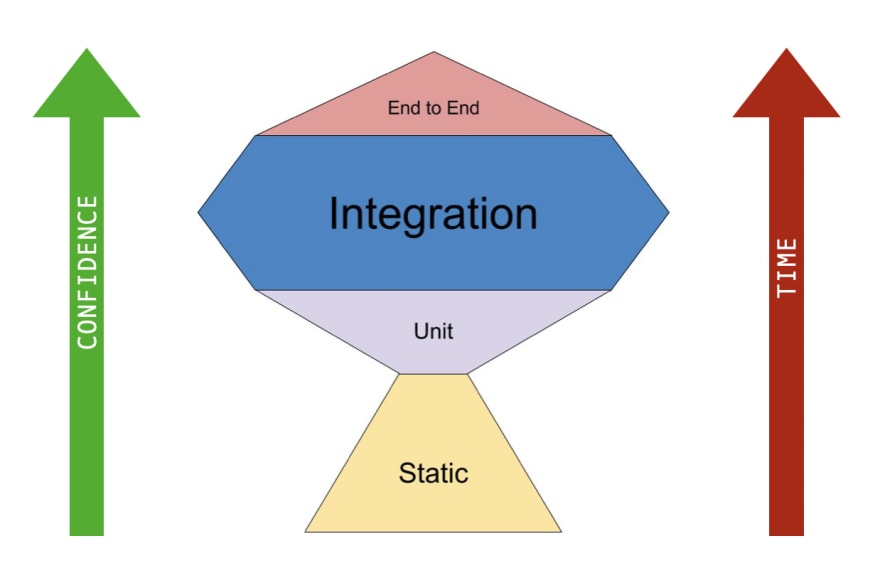

However, pushback against this model was proposed in 1999 at the height of popularity for Xtreme Programming (XP). Alternative models include Kent Dodd’s Testing Trophy

and Spotify Lab’s Testing Honeycomb.

As you can see, both models suggest that the majority of tests should be integration tests. These models responded to the change from monolithic architectures prevalent when Dodd proposed the Testing Pyramid to the shift to microservices and distributed architectures that make up modern applications.

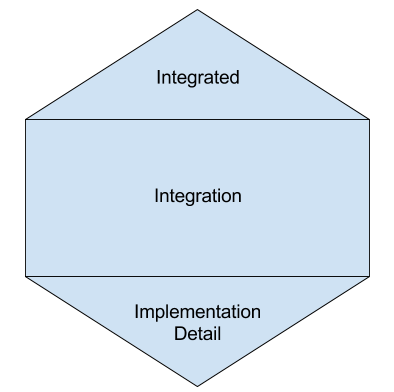

For deploying modern applications with cloud engineering, we propose an alternate model called the testing rocket. Static testing is inherent in cloud engineering because of the software toolchains, such as IDEs, that perform static checking. Both unit and integration testing are equally important to ensure that infrastructure is deployed and managed reliably. End-to-end tests for performance and scalability should be performed less frequently because of complexity and costs.

Cloud engineering testing

Cloud engineering applies software testing principles to infrastructure where we focus on functional testing. We use three types of functional tests with infrastructure: unit tests, integration tests, and property tests (sometimes called functional tests). We’ll examine each type of test in detail.

Static tests

Infrastructure templating languages such as YAML or JSON have limited static validation capabilities; primarily, they are limited to linting: validating and formatting the code. Pulumi’s approach of deploying infrastructure with programming languages lets you use built-in tools in IDEs that perform static tests, highlight errors in your code, and offer other features such as code completion, enumerations, and syntax checking. Pulumi’s preview also performs static checking before deploying a resource.

Unit tests

Unit tests for applications test the smallest piece of code, which are often methods and functions of classes or modules. They are commonly written by the programmer and run quickly.

With infrastructure, the smallest unit is often the cloud resource. Because cloud resources haven’t been created by the time you run unit tests, you can’t write a test to evaluate infrastructure behavior. For example, you can’t make HTTP requests to endpoints because there’s no web server to serve them.

Pulumi’s cloud engineering approach enables unit testing by replacing all external dependencies with mock objects that replicate the behavior in a specified way. This enables you to write fast unit tests that run in memory without any out-of-process calls. They provide rapid feedback loops during development, making them suitable for Test-Driven Development (TDD).

As with applications, unit tests for infrastructure in Pulumi are authored with the same language used to declare infrastructure. This means you can use familiar test and mock frameworks such as PyTest for Python or Mocha for Node.js. Using a framework ensures configuration is correct before provisioning and that the resulting infrastructure has the specified properties. In addition, team standards and security guidelines are enforced.

Property tests

Another type of test is property tests, which are sometimes called “functional tests.” Property tests evaluate the business requirements of an application by verifying the output of an action without examining the code that’s executed. Property tests, like integration tests, require components to interact. However, property tests require that the component return a specified value, while integration tests verify that the function works as required. For example, a property test would require a value, such as the count of rows returned, and an integration test would only require that rows are returned.

Property tests in cloud engineering and Pulumi use Policy as Code to set guardrails and enforce compliance for cloud resources. In addition to authoring company-wide policies, It also enables another type of infrastructure testing where a policy becomes a property that a test can evaluate and assert. Property tests run before and after infrastructure provisioning and have access to all input and output values of all cloud resources instantiated in a Pulumi program. Unlike unit testing, property tests can evaluate real values from the cloud provider and not mocked values.

Finally, there are several ways to run property tests against any cloud environment. They can be configured as a persistent stack for acceptance testing, or as an ephemeral cloud environment created by a pull request, or a combination of both.

Integration tests

Integration tests validate whether services or modules in an application work as specified. Unlike unit tests, they use actual dependencies instead of mock objects, and they provide less precise feedback than unit or property tests. Because integration uses actual dependencies, they require that services be complete and functioning. Tests are run in a strict order to ensure that modules or services are instantiated before the test. Developers are less likely to write and run integration tests, leaving it to SRE experts in specialties such as chaos engineering and pipeline automation to write tests run in a CI/CD system.

In cloud engineering, an infrastructure integration test uses infrastructure deployed in an ephemeral environment. As an example, we can use the Pulumi CLI to deploy the ephemeral environment as a stack that builds a dependency graph based on inputs and outputs that ensures the required resources are instantiated and available before the integration test.

Once the resources are deployed, the integration test retrieves the stack outputs, which is often a public IP address or resource name. The test can be as complex as a suite of application-level tests between the various services or components or as simple as a health check that expects an HTTP 200 status return from an endpoint. The primary advantage of integration tests is that they use the same cloud infrastructure used in production to return actual values.

However, there are two areas of concern. First, deploying ephemeral infrastructure takes time to create the resources. The impact is that integration tests are not performed as frequently as unit tests raising the possibility of finding bugs later rather than sooner. Secondly, there is a cost to deploying ephemeral infrastructure, and you can easily overrun your testing budget if performed frequently.

Distributed architectures have become the norm for cloud-based applications. For example, microservices are composed of individual services interacting with each other. Because of the interaction between stand-alone services, we can see why both the trophy model and the honeycomb model of testing prioritize integration testing despite these concerns.

Summary

Testing is an integral part of cloud engineering. With its origins in software engineering, we can use the same methodologies to build reliable infrastructure. We’ve presented three types of tests for infrastructure deployed with programming languages. When we use a programming language for infrastructure deployment, we can take advantage of the software toolchain to perform static tests not possible with templating languages. We can also perform unit tests and property tests without deploying infrastructure by using mocks and policies. Finally, we can build ephemeral infrastructure to perform integration tests at the application level. We’ll look at specific examples for performing unit, property, and integration tests in the follow-up article. Stay tuned.